There is a lot of discussion today about living what some theologians call the “Christoformity ” or the “Cruciform” life. Now I realize there is a variety of folks who use these novel words in different ways. But, at the core, I think most use these terms to emphasize at least three things:

the need to live our lives with Christ at the model,

the need to put Christ at the center of our theology, AND

the need to reinterpret the Bible with Christ at the center.

At least in the case of thing 1 and thing 2, this “new” idea of Cruciformity reflects what many theologians have said for a long time. Take Charles Spurgeon’s devotional, Christ at the Center, based on John 5:39. Spurgeon affirms the need for thing 1 when he writes:

Jesus Christ is the Alpha and Omega of the Bible. He is the constant theme of its sacred pages; from beginning to end they bear witness to Him. At the creation we immediately recognize Him as one of the sacred Trinity; we catch a glimpse of Him in the promise of the woman’s seed; we see Him pictured in the ark of Noah; we walk with Abraham as He sees Messiah’s day; we live in the tents of Isaac and Jacob, feeding upon the gracious promise; and in the numerous types of the law, we find the Redeemer abundantly foreshadowed. Prophets and kings, priests and preachers all look one way—they all stand as the cherubs did over the ark, desiring to look within and to read the mystery of God’s great propitiation. Even more obvious in the New Testament we discover that Jesus is the one pervading subject.

It is not that He is mentioned every so often or that we can find Him in the shadows; no, the whole substance of the New Testament is Jesus crucified, and even its closing sentence sparkles with the Redeemer’s name. We should always read Scripture in this light; we should consider the Word to be like a mirror into which Christ looks down from heaven; and then we, looking into it, see His face reflected—darkly, it is true, but still in such a way as to be a blessed preparation for one day seeing Him face to face.

The New Testament contains Jesus Christ’s letters to us, which are perfumed by His love. These pages are like the garments of our King, and they all bear His fragrance. Scripture is the royal chariot in which Jesus rides, and it is paved with love for the daughters of Jerusalem. The Scriptures are like the swaddling clothes of the holy child Jesus; unroll them, and there you find your Savior. The essence of the Word of God is Christ.

Cornelius Van Til affirms thing 2—the need for “Cruciform” theology—in that he believes the error of Western thought is the failure to put Christ at the center:

We shall indicate in those chapters what we believe to be the dilemma of all western thought. We hope to show that both the friends and the enemies of the Reformation fail in their efforts because they refuse to put the self-attesting Christ at the center of their system. In failing to do this, even the friends of the Reformation become its enemies.1

Hawthorne, connects both thing 1 and thing 2 to Paul’s theology.

For Paul, then, to reject the crucified Christ and live a life not shaped by the diaconal character of Jesus and its cruciform pattern as the sole means of salvation is in effect to reject salvation.2

I think Spurgeon, Van Til, and Hawthorne offer a sound biblical theology of the Christian life. However, Christoformity is more than just modeling the life of Christ. The problem I want to bring to light is not with thing 1 or with thing 2. Instead, I want to look at thing 3 and the problem that arises when we try to put the cross of Christ as the center of our biblical hermeneutic. I’ll use Greg Boyd to illustrate my concern.

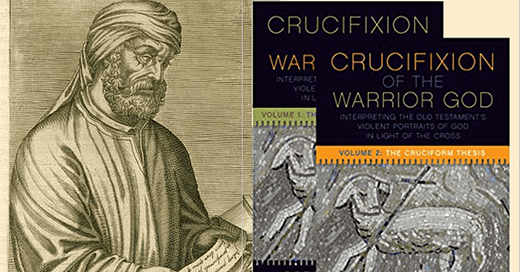

In his two volume series, Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Boyd offers a hermeneutic of “cruciform accommodation” in line with his belief that only the cross of Christ gives us a clear revelation of God as nonviolent. In Boyd’s view, Jesus’ teachings and actions show his “willingness to repudiate and renounce the Old Testament (pp. 67–84).”3 Consequently, Boyd believes that every passage in the Old and New Testament must be reinterpreted through this single act of Jesus’ love. Let’s look then at one example of Boyd’s Cruciform hermeneutic at work in the prophecy of Samuel.

1 Samuel 15:2–3 (ESV) Thus says YHWH of hosts, ‘I have noted what Amalek did to Israel in opposing them on the way when they came up out of Egypt. 3Now go and strike Amalek and devote to destruction all that they have. Do not spare them, but kill both man and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey.’”

Boyd looks at 1 Samual 15 and concludes that there is no way YHWH would have made such a wicked command. Why? Because, Boyd says, the Jesus of the cross would have never asked Israel to slaughter the Amalekites for something their king did 400 years earlier. After all, he argues, the Amalekites were only trying to protect their land from the invading Israelites so why would God punish these people for protecting their homeland? So, Boyd concludes, Samuel’s statement “Thus says YHWH” is not a command of God, but only Samuel’s “perception” of God as a warrior.

Boyd believes that Samuel’s false perception of YHWH as a warrior was not rooted in divine revelation, but based on Israel’s cultural misperception of God. Like all other peoples of the ancient Near East, Israel valued violent deities

But don’t worry, writes Body, even though Samuel gives Israel a false revelation, the core of the Old Testament still tells us something true about God’s character.

God’s very decision to further his purposes through a particular nation that would be established in a particular land, that would be governed by violently enforced laws and defended with violence, was itself a huge accommodation on God’s part (Crucifixion of the Warrior God, 727)."

God allowed Israel to follow these false prophesies of “Thus says YHWH” so that one day God could lead Israel to the cross of Jesus. This interoperation of 1 Samuel 15, for Boyd, is what it means to have a Cruciform hermeneutic.

This examination of 1 Samual 15 leads me to the helpful critique of Boyd’s hermeneutic from Wheaton College professor M. Daniel Carroll. Carroll’s talk titled, Reflections from a Christotelic Pacifist on Greg Boyd’s Christocentric Pacifism, was given at the 2018 meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society, in Denver, CO. In his talk, Carroll brings out three concerns I’d encourage every Christian to consider before shoving all-in on Boyd Cruciform gambit.

1. Boyd’s Cruciform Hermeneutic is too Simplistic

As an Old Testament scholar, I found myself disagreeing with Boyd at multiple junctures. He uses dated sources, misunderstands or overstates certain concepts in the Old Testament as they sit against the ancient Near Eastern background, and offers flat readings of texts.

Because Boyd needs to shove every Bible text through the single filter of the cross, he ends up ignoring important historical context and other theological filters present in the Old Testament. Boyd’s “flat” reading results in a deformed and over-simplistic reading of the text.

2. Boyd’s Cruciform Hermeneutic Privileges Modern Morals Over Divine Justice

Boyd has taken a slice of the kinds of reactions of God in the Old Testament and generalized it to be the only way God truly acts. His cruciform hermeneutic is a limited (but very logical!) post-eventum, post-crucifixion theological construct that does not respond to the cries of the Israelites suffering in Egypt, to the starving mothers in the siege of Jerusalem, or to the children on the streets of Aleppo. In short, his kind of logical Christocentric pacifism cannot provide tangible hope in divine action except in a limited way. Importantly, even the New Testament does not read the Old Testament in the limited way Boyd wants to.

This concern is twofold. First, Boyd uses his personal sensibilities about “love” to reinterpret the text. Boyd’s hermeneutic puts America’s cultural values and human perception at the center of biblical meaning.

Second, Boyd’s reading of the Old Testament makes God impotent to judge evil. For Boyd, God’s love would never end in judgment against the sin of the Amalekites and, therefore, Samuel must have been wrong to claim, “Thus says YHWH.” Boyd’s centering of progressive values to interpret the Bible leads to my third concern.

3. Boyd’s Cruciform Hermeneutic Makes Old Testament Prophets False Prophets

Boyd reads allegorically back into the Old Testament to demonstrate what he believes is the consistent presentation of God in the Bible, yet in so doing he effectively denies that the Old Testament revelation was true in those contexts, since it awaited clarification centuries later

In the case of Samuel, let’s not downplay the tragic implications of Boyd’s argument. The Cruciform hermeneutic means that when Samuel says. “Thus says YHWH” he could not really be speaking for God. Samuel’s words to Israel were nothing more than a cultural norm veiled in the garb of prophetic authority.

Given Boyd’s cruciform hermeneutic,, every Old Testament prophet offered half-truths dressed up as divine commands. These prophets could not see YHWH through the cross of Christ and so they remained victims of their ancient worldview.

While Boyd’s pacifist God may appeal to modern values, Trevor Laurence reminds us just how radical Boyd’s Cruciform hermeneutic really is.

Boyd laments that no one has interpreted the Old Testament in the manner he proposes (pp. 137–38), but perhaps the reason why Boyd’s reading of the Old Testament has not emerged in the church is simply because neither Jesus nor the New Testament authors read the Old Testament that way.4

I’d encourage all my brothers and sisters to give careful consideration to how they use these “new” terms such as “Christoformity ” or “Cruciform.” In consideration of thing 1 and thing 2, there is most certainly some good theological value to making Christ the center. That said, when it comes to thing 3, we must be careful not to use good theology as an excuse to invent a culturally sexy hermeneutic that deforms the historical and eternal meaning of the Bible itself.5

Cornelius Van Til, A Christian Theory of Knowledge. (The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company: Phillipsburg, NJ, 1969).

Hawthorne, Gerald F. 2004. Philippians. Vol. 43. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word, Incorporated.

Laurence, Trevor. 2017. “Systematic Theology and Bioethics. Review of The Crucifixion of the Warrior God: Interpreting the Old Testament’s Violent Portraits of God in Light of the Cross by Gregory A. Boyd.” Edited by Hans Madueme. Themelios 42, no. 3: 560.

Ibid.

The following quote from Laytham is presented as a positive, but here again I think it illustrates how Cricformity is used to distort ethics. Note also how Laytham conflates thing 1, 2, and 3 above to make his case. “Narrative ethics works with a consciously christological hermeneutic of both Scripture and the moral life. The quintessential display of this is Yoder’s Politics of Jesus, a book that irrevocably ties the story of Jesus’ nonviolent fidelity to cruciform, ecclesial discipleship. Thus, the gospel not only identifies God but also thereby convokes and characterizes a peculiar people of God who live conformed to God’s story. For both church and disciple, Christ is our life (Col. 3:4).” See, Laytham, D. Brent. 2011. “Narrative Ethics, Contemporary.” In Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics, edited by Joel B. Green, 538. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.