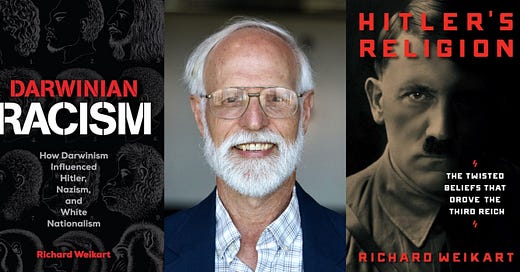

In Robert J. Richards’s essay in Darwin Mythology, he takes aim at my scholarship, especially my recent book, Darwinian Racism: How Darwinism Influenced Hitler, Nazism, and White Nationalism, which demonstrates that important elements of Hitler’s worldview were shaped by Darwinian theory. In the introduction to his essay, Richards claims that

“scholars of religious disposition (Berlinski and Weikart, for instance)” who try to link Darwin’s biology and Hitler’s racism “apparently intend to undermine evolutionary theory and morally indict Darwin and his allies, like Ernst Haeckel.” (p. 230)

There are two glaring problems with this statement by Richards, both of which are presumably caused by him jumping to (unwarranted) conclusions. First, he is blithely unaware that Berlinski is an agnostic, not a “scholar of religious disposition.” Second, he is misguided in claiming that my scholarship is based on an intent “to undermine evolutionary theory.” In fact, Richards will apparently be surprised to learn that I thoroughly agree with his assertion that Hitler’s belief in Darwinism is completely unrelated to the truth or falsity of Darwinism. My own rejection of Darwinian theory was based largely on an investigation of scientific data, and Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture focuses most of its energy on scientific arguments for Intelligent Design.

So, why then have I spent so much time and energy dealing with the intellectual links between Darwin and Hitler?

Let me start by providing an autobiographical sketch of how I came to study this topic so intensively. When I began my doctoral studies in modern European intellectual history, I intended to focus on nineteenth-century Germany. I was dismayed to learn that the professor I wanted to study under had a job offer elsewhere, so he would not be able to supervise my dissertation. He suggested I study under the department’s historian of science, who specialized in Germany.

Before that time, I had not even thought about focusing my research on the history of Darwinism. However, once I found out I would be studying under a historian of science, it just made sense to try to find a topic about the history of science in Germany. While looking for a topic, I happened to read Alfred Kelly’s work, The Descent of Darwin, about the popularization of Darwinism in Germany. His work convinced me that the history of Darwinism in Germany was underexplored in the scholarly literature.

Over the next few semesters I decided that my dissertation would be on the reception of Darwinism by German socialists in the late nineteenth century (it was titled, Socialist Darwinism). While researching this topic, I was struck by how some German Darwinists wanted to replace Judeo-Christian ethics with evolutionary ethics. I had long been interested in the history of ethical thought, so I decided this would by my next major research project: the history of evolutionary ethics in Germany in the late nineteenth century.

After receiving my Ph.D. in 1994, I began investigating the history of evolutionary ethics in Germany. Two things happened that altered the trajectory of my research: First, I soon discovered that many of the proponents of evolutionary ethics in the 1890s and early 1900s tied evolutionary ethics to other ideologies, such as scientific racism, eugenics, euthanasia, and militarism. The more I read, the more it seemed that these ideas were similar to Hitler’s ideology. In the early phases of my research, I had not even been thinking about Hitler.

Indeed in graduate school I thought that Hitler and the Nazi period had already been explored by more than enough historians, so I had no interest in focusing my scholarship on it. However, once I began investigating Hitler’s ideology, I discovered that his worldview was shaped by evolutionary ethics, and some central parts of his ideology were based on Darwinism. Though many historians had already called Hitler’s ideology social Darwinism, none had really put all the pieces of the puzzle together to show how Darwinian theory fed into the Nazi worldview.

Secondly, I read the philosopher James Rachels’s book, Created from Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism, in which he claims that Darwinism undermines the Judeo-Christian sanctity-of-life ethic, thus legitimizing abortion, infanticide, assisted suicide, and euthanasia. I was struck by how Rachels’s position was very close to some of the ideas I had encountered among nineteenth-century German Darwinists. The leading German Darwinist, Ernst Haeckel, for instance, had promoted euthanasia on the basis of Darwinism already in 1870.

Rachels’s book caused me to investigate the question: Has Darwinism contributed historically to a devaluing of human life? My research on this theme has explored the connections between Darwinism and Nazism, but I have also investigated the ties between Darwinism and racism, eugenics, and euthanasia in other historical periods and places, too.

But what difference does all this make anyway? Why should we care whether Darwinism influenced Hitler or not? I’ll answer that question in Part 2.